The Invited Philosophers

Gilles & Fred

This was the 19th dinner, at my house, and because Gilles missed the Tertulia and everybody loved the grilled Shawarma chicken, I repeated the menu for this event.

Menu

- Appetizers: Rice crackers and pita chips with spinach and artichoke cream.

- Main course: Grilled chicken shawarma, Moroccan couscous, tzatziki sauce, and mixed green salad.

- Desserts: Pastries from a Portuguese bakery (Courtesy of G&F).

- Drinks: Champagne Ernest Rapeneau (Courtesy of G&F) and Maison Barboulot Cabernet-Syrah.

The Philosophy

René Descartes (1596–1650) defined his philosophy of the “Passions of the Soul” with the help of his pen pal and fellow philosopher Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. It is important to note that by “soul” Descartes meant the “mind”. According to Descartes, sensations, appetites, and passions have a practical functionality: to act as guides for maneuvering our bodies through the world, and ultimately for preserving the mind-body union that constitutes the human being. Elisabeth and Descartes discuss how such metaphysically disparate things as mind and body can act on each other, and by 1645, their discussion shifts to whether the mind can control the body, particularly its passions. Descartes diagnoses a “low-grade fever” from which Elisabeth had been suffering as caused by sadness or melancholy, and recommends the familiarly Stoic-sounding remedy of reading Seneca, while reflecting on her mind and its ability to master bodily-based passions. In this conversation, Elisabeth raises an important question:

“Even if some people manage resolutely to overcome the passions and achieve happiness, is it possible to do so ‘without the assistance of that which does not depend absolutely on the will’?” (And here she meant external situations)

It is important to point out that Descartes declares that mind and body form a “substantial union”, although at the same time he proposes a clear and distinct concept of the mind “on its own as a complete thing”. He also declares that “what is a passion in the soul is usually an action in the body” and identifies them as the “same thing”. In general, the “principal and most common causes” of passions are objects, considered according to “the various ways in which they may harm or benefit us, or in general have importance for us”.

The Summary

Descartes proposes that our sense-perceptions, appetites and passions of the mind enable us to experience ourselves as embodied humans, inside a “mechanical body” as Descartes labels it, in contrast to the immaterial mind. Passions enable my body or “my-embodied-me” to be spatially located relative to other objects (including other humans) and interact with them. The passions are linked to judgments, e.g., something is good for my-embodied-me, or poses a risk for my-embodied-me. Passions of the mind navigate our mechanical bodies through the world.

Descartes identifies six “primitive” and distinct passions: (1) Wonder, which he calls “the first of all the passions,” (2) Love and (3) Hatred, (4) Joy and (5) Sadness, and (6) Desire. All passions, except for wonder, exhibit attraction to or aversion of the objects they evaluate. This leads to the opposition of love to hatred, and joy to sadness. Desire has no opposite, since it comprises both attraction and aversions, and is solely directed at the future.

Each of the main passions receives a detailed description of the bodily changes that accompany it, such as changes in color, body temperature, facial expression, disposition of the limbs and the like.

Descartes locates passions squarely in perception, although he also calls them “emotions” (motions, changes, agitations, disturbances). As described in the Stanford philosophy article:

Descartes also accepts variations and combinations of the six primitive passions but he focuses more on a passion’s intensity (timidity is different from terror), whether its object is oneself or another (self-esteem differs from veneration), and in further modifications of the object and its relation to us (love is distinguished from the devotion we feel for an object “greater” than we are, such as God). Descartes allows even contrary mixtures as in hope and fear. Passions seem to ‘combine’ most readily by producing trains of passions: desire may give rise to love, which may in turn generate joy. Trains of passions may involve passions with contrary directions, but this produces the rather uncomfortable sensations of remorse, or repentance.

Analysis

Good and Bad Judgements

This is the second time Gilles joins one of my dinners and each time, I select a French philosopher for him. As usual, Gilles did his homework very thoroughly by listening to French podcasts, such as this part 1 and part 2 compilation of Les passions de l’âme. In this context, l’âme is not translated as “soul” but as “mind”.

Gilles explained that according to Descartes, the function of the mind is to provoke judgements and to identify what is good or bad for our mechanical body. The mind does not look for good or bad experiences. It merely judges but it may judge incorrectly based on past experiences generated by previous judgements. True wisdom does not make errors in judgement, but as a consequence of our opinions, culture, and experiences, we can make mistakes and misjudge. Misjudgements occur in our pursuit of virtue. I argue that these mistakes occur because we never clean out the junk in our “thought-hoarding cave”, which is where we collect past memories that we trust as a guide without ever considering their value.

When discussing bad judgments, I need to point out a famous but erroneous phrase by Descartes that we will not fully analyze here but needs to be mentioned: “I think, therefore I am”. If Descartes had done this simple thought experiment, he would have realized his error, that he is not his thoughts: “I can observe my thoughts. I can observe my mind being occupied with one thought after another. I can also observe it being quiet. And when I observe this, who am ‘I’? Who observes the thoughts?”

Wonder and Virtue

This leads very nicely into the discussion of the passion of wonder and virtue. Wonder does not involve judgment, it often involves no thoughts! Wonder, also called admiration, merely presents its object as something novel or unusual. Descartes states that wonder, unlike other emotions, doesn’t trigger physical action but leaves a lasting memory by imprinting the experience on the brain. And that explains the function of wonder: to “learn and retain in our memory things of which we were previously ignorant”.

I would argue that “wonder” is the most wonderful passion of the soul! I would also argue that there is love and joy in wonder. Moreover, and my next observation contradicts Descartes’s philosophy a little, but only a little because it also involves “desire”: I know the desire to experience wonder does move our mechanical bodies! We experience wonder when we travel and see new sights and how wonderful that feels! There is a whole travel industry dedicated to that kind of wonder.

Another distinctive passion Descartes describes is generosity, which produces a kind of self-directed wonder, or esteem, grounded in our recognition that true generosity lies not in material possessions but in mastering our will. It is a form of self-esteem that involves recognizing that only our choices are truly ours and that we should use that freedom wisely. Gilles shared that he has no fears because he trusts in himself, and like he learned as a child, he always does his best to ensure he has no regrets. He has learned that you cannot depend or control the external world. Or as Fred puts it, if you try to control the world you become a slave of the world, because you depend on others to fulfill your wishes or needs.

Descartes sees “generosity” as the key to pursuing virtue. It allows us to control our emotions and act according to reason. This self-mastery extends outwards, making generous people kind and free from negative emotions like jealousy or anger. The core principle seems to be that by understanding what truly matters and having the willpower to act accordingly, both towards ourselves and others, we achieve true emotional control. Descartes identifies the remedy for disorders of the passions [les dereglemens des Passions] quite generally with virtue, and virtue with happiness.

Descartes may be the father of “Positive Thinking”: In order to combat negative emotions, Descartes suggests a strategy of using imagination. By picturing a different outcome or response to a situation, we trigger brain activity that can indirectly influence our body’s natural reactions and lessen the power of unwanted feelings.

What about Passionate Love?

Descartes describes love as a passion involving a “consent by which we consider ourselves from the present on as joined with which we love, in the sense that we imagine a whole of which we think of ourselves only as one part and the loved thing as another” (AT XI 387, modified from CSM I 356). He does not limit love to love between people but also of inanimate objects. Our own body may become the object of passionate love and care when bodily health elicits love and joy in the soul.

At the start of dinner, I played an excerpt from a French audiobook by Anthony De Mello that reminds us that falling in love is not love. It is rather a burning desire to join with the other person. De Mello explains:

When we find someone who fits our vision of the ideal partner, we may fall in love, but have we truly seen this person? No. We will only see this person after a certain time of getting to know each other. But it is then also, that true love can begin.

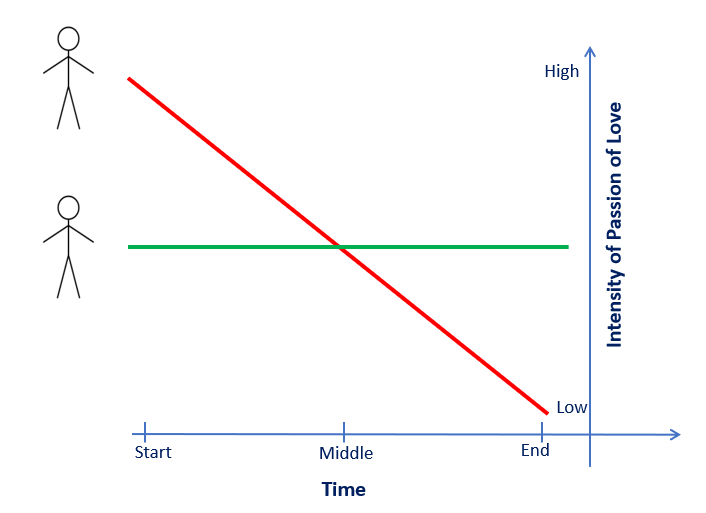

In my opinion, if love has an opposite, it is not true love. If joy has an opposite, it is not true joy. If the intensity of love diminishes, then it is not true love, rather, it is just passion, the experience of falling in love and falling out of love. Be aware when that happens to you or others. True love is steady, never too high, never too low. In the graph below, true love is represented by the green horizontal line, it is steady. Infatuation and passion is represented by the red line.

I would suggest that living life in constant wonder and awe about our experiences in the world, without judging, without generating hatred, fear, or sadness in oneself or others, is the true essence of love. Descartes was right in connecting good judgment to virtue and using both to solve the problem of getting carried away by our passions. By always doing our best, we are virtuous and generous to others, which is love. But a better solution that leads to true and unconditional love is to stop all judging, to live in wonder and acceptance of (the experience of) others and the world, and to avoid being tempted by our senses or desires.

If you close your mind in judgements

and traffic with desires,

your heart will be troubled.

If you keep your mind from judging

and aren’t led by the senses,

your heart will find peace.

― Tao Te Ching – Verse 52